Native Americans And HorsesThe story of the relationship of Native peoples and horses is one of the great sagas of human contact with the animal world.Native peoples have traditionally regarded the animals in our lives as fellow creatures with which a common destiny is shared.

When American Indians encountered horses—which some tribes call the Horse Nation—they found an ally, inspiring and useful in times of peace, and intrepid in times of war.

Horses transformed Native life and became a central part of many tribal cultures.

By the 1800s, American Indian horsemanship was legendary, and the survival of many Native peoples, especially on the Great Plains, depended on horses.

Native peoples paid homage to horses by incorporating them into their cultural and spiritual lives, and by creating art that honored the bravery and grace of the horse.

The glory days of the horse culture were brilliant but brief, lasting just over a century. The bond between American Indians and the Horse Nation, however, has remained strong through the generations.

“A Song for the Horse Nation” Gallops into Washington

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., presents a major exhibition that explores one of the greatest sagas of human contact with the animal world—American Indians and horses.

“When American Indians encountered horses—which some tribes call the Horse Nation.

they found an ally, inspiring and useful in times of peace, and intrepid in times of war,” said Kevin Gover (Pawnee), director of the museum.

“The exhibition shows how these majestic creatures came to represent courage and freedom to many tribes across North America.”

The critically acclaimed exhibition, first shown at the museum’s George Gustav Heye Center in New York (Nov. 14, 2009-July 10, 2011), doubles its exhibition space at the flagship museum on the National Mall to 9,500 square feet and includes 15 major additional objects.

Among them is a 19th-century, 16-foot-tall, 38-foot-circumference Lakota tipi, in which 110 hand-painted horses, some with riders, all at a full gallop, cover the entire surface in rich reds, turquoise blues and golds as vivid and fresh as the day they were created.

These battle and horse-raiding scenes proclaim the heroic deeds of the warrior who once lived in the tipi.

The exhibition shows how Native horse traditions continue today like the Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) Young Horsemen’s Program, which seeks to preserve the Appaloosa horse breed made famous by their ancestors.

Horse traditions thrive on the Crow Indian Reservation—their annual fair in southeastern Montana typically includes more than 2,000 horses and features elaborate parades and “giveaways” in which members of the tribe give away horses to relatives and friends as a gesture of generosity and honor.

A similar gesture among the Lakota is the tribe’s annual trek on horseback called the Oomaka Tokatakiya

(Future Generations Ride) in South Dakota, which evolved from an annual healing journey to honor those who died at Wounded Knee.

During the two-week, 300-mile journey, riders experience some of the hardships their ancestors endured as a physical, spiritual and intellectual remembrance.

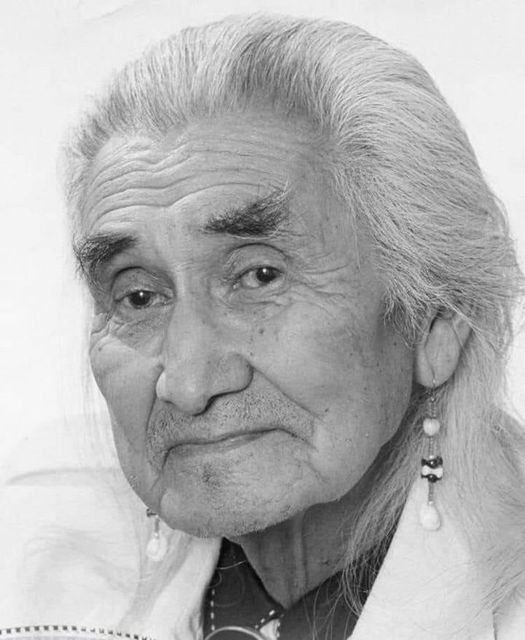

“For some Native peoples, the horse still is an essential part of daily life,” said Emil

Her Many Horses (Oglala Lakota), curator of the exhibition.

“For others, the horse will always remain an element of our identity and our history.

The Horse Nation continues to inspire, and Native artists continue to celebrate the horse in our songs, our stories and our works of art.”